Designing for your hypothesis

How is designing for an experiment different from designing a feature?

When you design for an experiment, your role as a designer is to focus on testing the hypothesis. In this process, design priorities may shift from what we typically consider in a traditional design process. While feature design emphasizes delivering a polished and scalable solution, experimentation entails creating a controlled environment to test hypotheses effectively. This requires the designer to fully facilitate conversations between different disciplines and embody a comprehensive understanding of the product.

In summary, designing for experimentation involves strategically balancing bold exploration with controlled execution. In this section, we highlighted our understanding of key principles and considerations in each phase of designing user experience specifically for experimentation.

The Design role usually starts with defining the MVP or MVT (minimum viable test) in collaboration with the Product team. We can break this process into

1) Design the right thing (Exploration) and 2) Design things right (Delivery)

Exploration

In this phase, our role as designers is to be facilitators. Our goal is to leverage tools such as visualization and critical thinking to help define our problem or opportunity and identify potential paths for defining the scope. Following these principles aids us in arriving at a conclusion.

01. Go back to the “why”

When conducting experiments, we often lack a clear problem definition and a defined scope, which can lead us to get lost in endless design possibilities. This may result in a departure from the original intentions of the experiment. Having a clear understanding of the “why” (goal, opportunity, hypothesis…, etc.), “who” (the user persona), and “when” (eg: Activation moment) helps us identify the “what” (solution) and avoid getting lost.

02. Leverage bold ideas

Experimentation offers a unique opportunity to take creative and business risks. Treating an idea as an experiment allows designers to explore innovative strategies and test concepts that the team cannot guarantee will succeed. In the context of a feature launch, it's often too risky to proceed with a full-scale product launch without solid data demonstrating its potential benefits for the business. This experimental approach creates a "sandbox" environment that encourages innovation and exploration, as the team can closely monitor the idea's performance before deciding to launch it.

However, it's important to consider the development costs associated with these ideas. If developing a risky concept is too expensive, we should evaluate it qualitatively before committing resources to development.

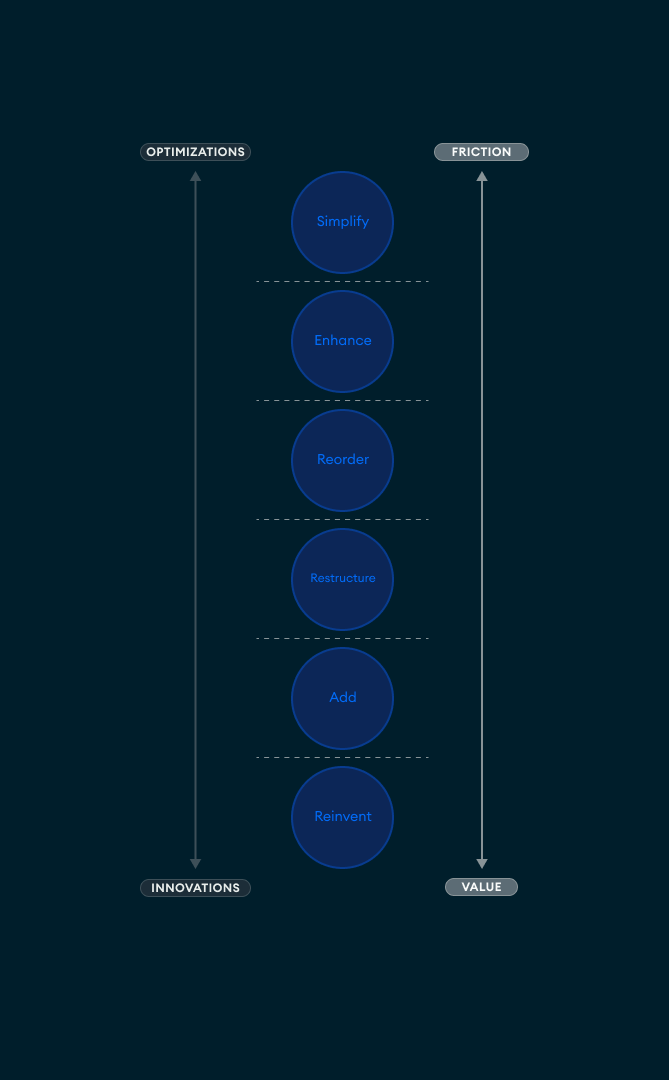

03. Differentiate between innovation vs. optimization

Identifying the category your project falls into can clarify your exploration and design process. Experiments generally fall into two categories: optimizations and innovations. Although the lines between the two can sometimes blur, understanding these distinctions can help your team focus on either leveraging new ideas or refining existing ones..

Innovation experiments focus on testing new value added to the ecosystem. This often involves reinventing or adding a feature. Occasionally, restructuring an existing feature to better communicate its value can also be considered innovation.

On the other hand, optimization experiments generally refer to smaller projects aimed at reducing usability friction by simplifying, enhancing, or reorganizing existing features.

a. Innovations (new experiences)

It's important to keep the experiment tightly scoped when exploring uncharted territory to isolate influencing factors. By maintaining a controlled environment, you can directly attribute the results to the specific elements being tested, ensuring the integrity of your findings. This approach may require additional effort in the design and product phases to prioritize the concepts you've developed before launching the experiment.

To prioritize the concepts and limit the scope qualitatively, consider using both unmoderated and moderated user testing to gather initial data and gauge direction. To determine the best co-design or testing methods, contact the User Experience Research (UXR) team for their recommendations.

b. Optimizing Existing Experiences

For enhancements, base your hypothesis on a solid understanding of the current experience. Insights into user behaviors and business outcomes reveal what works and what doesn't, allowing you to create targeted improvements. This will give you the leverage to make your hypothesis more targeted, thereby enhancing the experience.

As a general guideline for these experiments, it's crucial to act quickly and put your ideas into practice to evaluate their performance right away. You can safely launch the experiment without needing concept validation or usability testing beforehand. Once the experiment is live, monitoring metrics and analyzing the performance of the idea will help identify the next steps.

04. Prioritize Learning from Experiments

The success of an experimentation program is determined by the value it delivers and the insights it uncovers. An experiment can only be considered a failure if it doesn’t provide any new insights that were not previously known. To maximize this learning, keep the following three points in mind:

a. Make Significant Changes

Ensure that the changes you implement have a meaningful impact on the user experience. Minor adjustments, such as altering a button's label or modifying a tooltip, typically do not affect user experience enough to influence your metrics.

b. Drive Sufficient Traffic

When designing the full flow of the experiment, consider how to expose users to the new experience to gather enough data. In B2B services, there are often limitations on experimenting with pages that are rarely visited or are deemed edge cases. For necessary changes in these areas, it is advisable to treat them as JDIs (Just Do It) instead of using up experimentation resources. Additionally, consider adding an entry point to the new experience from a highly visited page to increase traffic and achieve faster results.

c. Focus on Your Hypothesis

Your primary goal should be to create a user experience that tests your initial hypothesis. Ensure that your changes are addressing this hypothesis rather than merely improving the existing user experience. It’s easy to become distracted by perfecting the design and lose sight of the original objective.

Delivery

In this phase, the focus shifts to executing the experiment with quality and efficiency. Based on our experience, we recommend following these principles:

01. Adhere to UX principles

Designing for experimentation still requires delivering a thoughtful and complete user experience. As designers, we should prioritize usability, user delight, and optimized workflows as our primary focus.

Tip: For a collection of best practices, refer to Laws of UX.

02. Prioritize core UX over perfection

Experiments inherently risk negative results, making it crucial to manage design and development investment carefully. Focus on delivering the essential experience needed to validate your hypothesis. You can postpone polishing edge cases, anomalies, or visual refinements until after the experiment’s success is confirmed. This is typically done during the “wrap-up” phase before full production launch, when refinement opportunities are reassessed with stakeholders.

03. Gather feedback efficiently

Experiments often operate under tight timelines, so gathering feedback efficiently is key. When presenting designs:

Set clear context: Frame the hypothesis early to focus the audience’s attention on the specific test, not unrelated possibilities.

Invite the right team: Include PMs, engineers, and analysts directly involved in the experiment. Every discipline can help assess if the design would negatively impact the data gathered or the infrastructure.

Present at two key points:

Early-phase review: to course-correct if needed.

Finalization review: can be async or live, depending on team preference.

03. Prepare for the wrap-up

After the experiment launch and waiting period to watch the analysis, it’s time to decide the fate of the design. In B2B, this usually happens many months after you are done with the design. In case of success, the team might decide to launch for prod immediately to impact business positively; in this case, you won't have time to rediscover potential missed opportunities. To make it easier for quick actions, there are steps you can take while designing.

Not doing list: To avoid confusion about issues or opportunities not addressed in the initial design, maintain a visible “Not Doing” list in your design files. You can also incorporate a checklist into the Product Document (PD) to clarify design considerations. This documentation will be helpful during the wrap-up phase, allowing you to revisit deferred improvements if the experiment is successful and prepare for the final production launch.

Wrap-up item list: Some feedback that does not directly impact the hypothesis testing scope can be parked for the wrap-up phase. This feedback usually addresses potential for experience perfection, edge cases, and copy improvements.

Live experiments list: Consider the case where there are other experimental results/product launches that would impact the final product experience. Usually, during the optimization experiment process, there might be another experiment on the target touchpoint that might also “win” and be launched before your successful experiment. Getting a list of other possible changes during your design phase will help you consider those potential changes during the design.